"When a man falls before God in prayer, he is like one dead to the world, hoping only in the mercy of the Lord to raise him up. Every time you fall, rise again, for it is through rising that man enters the Kingdom." St. Isaac the Syrian (7th century), Ascetical Homilies

Prostrations (metanoiai, meaning "change of mind" in Greek) are a fundamental part of Eastern Orthodox Christian ascetical practice, particularly during Great Lent and other periods of repentance. A prostration is a full-body movement of bowing, kneeling, and touching the forehead to the ground, signifying humility before God. This physical act is deeply tied to repentance, worship, and spiritual struggle, reflecting both biblical traditions and the teachings of the Holy Fathers.

Throughout Orthodox history, prostrations have been regarded as an essential part of bodily prayer, embodying the unity of soul and body in worship. They serve as a means of expressing repentance, subduing the passions, and offering oneself in complete humility to God. Their use is particularly emphasized during Great Lent, the Prayer of St. Ephraim, monastic life, and personal spiritual discipline.

1. Biblical Foundations of Prostrations

Prostrations are deeply rooted in the Old and New Testaments, where bowing, kneeling, and falling to the ground are acts of worship, repentance, and submission before God.

A. Old Testament Precedents

Abraham fell on his face before God when God established His covenant with him (Genesis 17:3).

Moses and Aaron fell on their faces before the presence of God in the Tabernacle (Numbers 16:22).

King David prayed with a bowed posture, symbolizing humility and repentance (Psalm 95:6: "O come, let us worship and bow down: let us kneel before the Lord our Maker").

The Ninevites, at Jonah’s preaching, repented in sackcloth and ashes, using bodily expressions of penitence(Jonah 3:5-6).

B. New Testament Examples

Jesus Himself prayed prostrate in Gethsemane, saying, "He fell on His face and prayed, saying: 'My Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass from Me; nevertheless, not as I will, but as You will'" (Matthew 26:39).

The sinful woman who anointed Christ's feet knelt before Him in an act of repentance and devotion (Luke 7:38).

The Apostle Paul states that one day 'at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth' (Philippians 2:10).

The Book of Revelation describes the 24 elders falling before the throne of God in worship (Revelation 4:10).

Thus, prostrations are a biblical expression of humility, repentance, and reverence, used both in Old Testament temple worship and the early Christian Church.

2. Historical and Liturgical Use in the Orthodox Church

A. Early Christian and Apostolic Practice

The earliest Christians inherited Jewish bodily prayer traditions, including bowing and prostrations. By the time of the Desert Fathers (3rd–5th centuries), prostrations became a defining feature of monastic asceticism, symbolizing humility, penance, and spiritual warfare.

St. Anthony the Great (251–356) and the Desert Fathers emphasized prostrations as a way to combat the passions and attain spiritual vigilance (nepsis).

St. Basil the Great (330–379) affirmed the importance of bodily worship:

"Since we are composed of body and soul, and both come from God, we should offer to Him a double thanksgiving—our soul’s devotion and our body’s posture." (Homily on Psalm 29)

St. John Cassian (360–435) taught that prostrations helped unite the mind, soul, and body in worship.

B. Prostrations in Great Lent and the Prayer of St. Ephraim

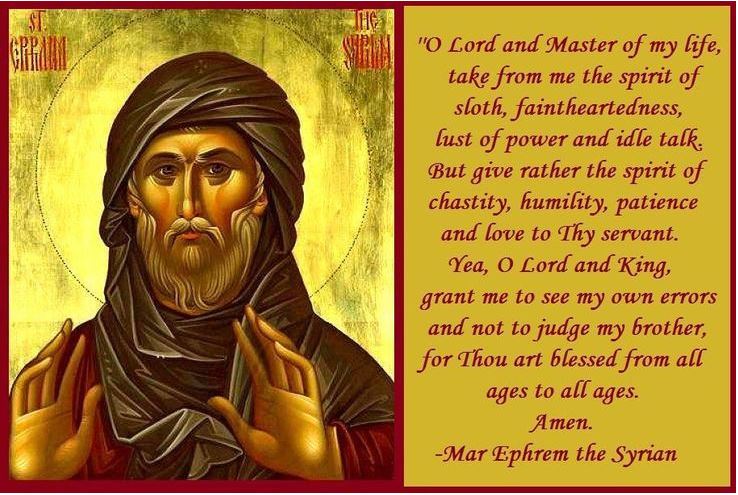

One of the most distinctive penitential practices involving prostrations occurs during Great Lent in the recitation of the Prayer of St. Ephraim the Syrian:

"O Lord and Master of my life, take from me the spirit of sloth, despair, lust of power, and idle talk…"

Each petition of this prayer is accompanied by a full prostration, reflecting deep repentance. This prayer is repeated daily during Great Lent, reinforcing bodily participation in the ascetic struggle.

C. Monastic and Personal Spiritual Practice

Monks and ascetics frequently use prostrations in their private prayer rule, performing hundreds of prostrations daily as an offering of repentance and spiritual discipline.

Laypeople are also encouraged to incorporate prostrations into their personal prayer lives, especially during times of spiritual struggle, confession, and fasting seasons.

3. Theological Significance of Prostrations

A. Expression of Repentance and Humility

Prostrations are a physical manifestation of repentance, echoing the biblical call to "humble yourselves before the Lord, and He will exalt you" (James 4:10). The act of lowering oneself to the ground symbolizes:

A return to dust (Genesis 3:19).

A recognition of God’s sovereignty and mercy.

A rejection of pride and self-sufficiency.

B. Participation of the Body in Prayer

Orthodoxy teaches that human beings are psychosomatic (soul-body) creatures, meaning that worship involves the entire person, not just the intellect. St. John of Damascus (675–749) states:

"Since we are not incorporeal beings like the angels, but bound by flesh, it is necessary that we approach spiritual contemplation through physical things." (On the Divine Images)

Thus, prostrations help align the body with the soul, ensuring that repentance is not merely internal, but physically enacted.

C. Spiritual Warfare and Victory Over the Passions

The struggle of Great Lent is a spiritual battle against sin and the passions.

The Desert Fathers saw prostrations as an act of self-denial and a way to "crush the devil" through humility.

St. John Climacus (579–649) in The Ladder of Divine Ascent describes bodily prostrations as a form of ascetic discipline that leads to purification of the heart.

D. Anticipation of the Resurrection

Prostrations symbolize death to sin, while standing up again represents rising in Christ.

This reflects baptismal theology: dying and rising with Christ (Romans 6:4).

4. Liturgical Guidelines and Exceptions

While prostrations are a normal part of Orthodox worship, Orthodox practice regarding prostrations varies by tradition and local custom, with some differences between Greek, Slavic, and other jurisdictions. A priest or spiritual father will provide guidance on when and how to perform them, especially during fasting seasons and liturgical services.

The following shows the canonical guidelines:

No prostrations on Sundays – The Lord’s Day is a celebration of the Resurrection, and thus, kneeling or prostrations are forbidden by the First Ecumenical Council (Canon 20, Nicaea 325 AD). Instead, bowing from the waist (metanoia) is permitted.

No prostrations from Pascha to Pentecost – The Paschal season is one of joy, and thus, full prostrations are suspended until after Pentecost.

5. Conclusion

Prostrations are an essential ascetical practice in Orthodox Christian spirituality, embodying the soul’s repentance, humility, and struggle against sin. Deeply rooted in biblical tradition, practiced by the early Church and monastics, and reaffirmed by the Holy Fathers, prostrations are a visible, physical expression of inner transformation.

They teach us that true worship is not just intellectual, but holistic—engaging the mind, heart, and body in a posture of surrender to God. As Orthodox Christians, we prostrate before the Lord in penitence, that we may rise with Him in glory at Pascha, the Feast of Resurrection.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.